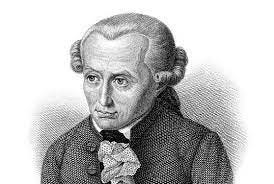

Where would Kant stand on The Trolley Problem?

18th century philosopher Immanuel Kant was known for his writings on morality, ethics, and metaphysics

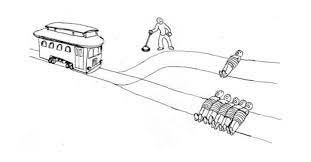

The Trolley Problem, initially proposed by Philippa Foot and so named by Judith Jarvis Thomson in a 1976 article, is a now common problem used in ethics and psychology. The problem shows an image of a trolley that is on track to run over and kill five individuals tied to the track. You see another track, with only one individual tied to it. But you as a bystander see a switch. If you flip the switch, you save the five individuals, but in the process of switching tracks the trolley runs over one person, killing them. So you are presented with the problem. Do you take an action to save five people by sacrificing one, or do you take no action and let the trolley run its course killing five people? There are many versions of the problem that have come about in the time since the problem originated, but the baseline stays the same: Is it worth taking action to save five individuals and intentionally sacrifice one person? There is no one right answer. How you react to the Trolley Problem comes down to one's personal moral beliefs. For Kant, he would not flip the switch because he would argue that killing is wrong. No matter what. So taking no action, and letting the trolley run its course, would be the best option. By creating a universal maxim (that killing is wrong, no matter what), that maxim must be universal. If you flip the switch, you are taking direct and deliberate action and killing someone. That breaks the universal maxim. In addition, the maxim can not be universal if you kill someone. So, to ensure that the maxim remains universal, Kant would argue against flipping the switch, even if more people die.

For Kant, the universal maxim is of vital importance. A maxim is a rule or principle which you abide and stand by. For the maxim to be universal, it cannot be broken. A universal maxim is based on the idea that if everyone follows and abides by the rule, then the maxim would remain universal, as it is applied to everyone equally, and that it would be sustainable in the long-term. Kant states, “The universal imperative of duty could also be expressed as follows: so act as if the maxim of your action were to become your will a universal law of nature” (Kant 34). In the example of the Trolley Problem, the universal maxim would be that killing is wrong. But for the time being, let’s reverse the maxim and assume that the maxim is that killing is good. If we take this assumption, that killing is in fact a good thing, then people would be able to go around killing other people. Just imagine the chaos that would take place. If that were the maxim, then the rule could not be broken. So in no instance could killing be a crime or be punishable. We would live in a society governed by violence. Assuming that the maxim is in fact that killing is good, it would not be sustainable in the long-term. Not even remotely. So we can then assume that the maxim would in fact be that killing is wrong, as it is the only sustainable way to create a maxim about killing. This maxim is one that is sustainable. We can live in a world where we collectively agree that killing is wrong, and that the punishment is for those that kill, not those that do not kill. To extrapolate that, this is what Kant would argue. So by not flipping the switch, he would be upholding the universal maxim. If he flipped the switch, and was directly and actionably responsible for someone's death, then he would have broken the universal maxim.

Some argue that Kant would flip the switch as a form of harm reduction. I do not believe that to be an accurate representation of Kant and his beliefs. Kant is very rigid in his beliefs. A universal maxim is a universal maxim, and as such must be kept universal. While we know that in reality situations like the Trolley Problem are never black and white, Kant’s philosophy and worldview was narrow and defined. I will recognize that the argument of harm reduction is one that makes sense. But in my opinion this overlooks the most basic understanding of Kant and his work, The Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals, which lays out rather clearly that the universal maxim creates the framework for any understanding of morality and ethics. This is not necessarily my personal belief, but it is my opinion of what Kant would argue. While Kant would not want to see five individuals die, he would not support deliberately taking action to sacrifice someone else. As in Kant's mind, those are one and the same. Death is death. Killing is killing.

An important part of Kant’s philosophy is the categorical imperative. The categorical imperative has two parts: one being the universal maxim, the other being Kant’s belief that people should not be used as simply a means to an end. When we think about what Kant means by not using people as a means to an end, it means that you don’t use someone, or complete an action, solely to get to an end. You must look at the route you take to get there. You must consider the people you are using. Kant says, “Act in such a way that you treat humanity, whether in your own person or the person of another, always as an end, and never simply as a means” (Kant 45). Kant would not support pulling the lever, as when you do this, you are using the people on the track, all six of them, as a means to an end. It doesn’t matter if this end will result in four less people dying, as in the process of doing so you are playing god. Kant would fundamentally oppose this:

It can lie nowhere else than in the principle of the will, without regard to the ends that can be effected through such action; for the will is at a crossroads, as it were, between its principle a priori, which is formal, and its incentive a posteriori, which is material, and since it must somehow be determined by something, it must be determined through the formal principle in general of the volition if it does an action from duty, since every material principle has been withdrawn from it (Kant 16).

While some would argue that pulling the lever is not in fact using someone as a means rather than an end, this argument is inherently flawed. The argument is that no one benefits from flipping the switch; therefore, Kant would view this as acceptable. I object to this notion. The second half of the categorical imperative is that one can not use people as a means to an end. Full stop. Kant left very little wiggle room, not just when it comes to this, but in general. Throughout the Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals Kant is fairly straightforward. One of the biggest things I noticed was that Kant leaves little room for gray areas. In his eyes, morality is black and white. This fundamentally puts down any theory that Kant would support harm reduction. Saying that, I recognize the moral gray areas in life. But Kant does not recognize those areas at all, which leads me to my argument that Kant would not flip the switch, and rather let the scenario in question play out. By not getting involved and taking action, you avoid using other humans as means to an end. Kantian ethics doesn’t recognize as many gray areas to morality, and this is one of those areas that is very much black and white.

Another interesting aspect of Kantian ethics to apply here is Kant’s opinion of what makes something morally good. For Kant, it is the reasoning behind the action, not just the action itself, that defines whether or not the person was making a morally good decision. Let’s look at an action that would normally be viewed as morally good: performing CPR on someone. To the average person, this action would be morally good. I’d go as far as saying this action could even be deemed heroic. I think most people would agree with that assessment of the action. But for Kant, it isn’t quite that simple. You have to look at the reasoning behind the action. Did the person performing the action do so out of pure instinct? Did they gain any happiness or sense of moral superiority from taking the action? If so, then the action is not morally good, even if it benefitted the general public and was an inherently beneficial action to take. Kant states:

To be beneficent where one can is a duty, and besides this there are some souls so sympathetically attuned that, even without any other motive of vanity or utility to self, take an inner gratification in spreading joy around them, and can take delight in the contentment of others insofar as it is their own work. But I assert that in such a case the action, however it may conform to duty and however amiable it is, nevertheless has no true moral worth, but is on the same footing as other inclinations, e.g., the inclination to honor, which, when it fortunately encounters something that in fact serves the common good and is in conformity with duty, and is thus worthy of honor, deserves

praise and encouragement, but not esteem; for the maxim lacks moral content, namely of doing such actions not from inclination but from duty (Kant 14).

When we look at the Trolley Problem through this lense, we would have to first know if the person pulling the lever was doing so out of any sense of wanting to earn praise or happiness. When we look at this problem, most people may feel pressure from other people to pull the switch as many people view doing so as harm reduction. If that is the case, then the action is not inherently moral, and Kant would not approve.

In conclusion, Kant would not pull the lever. By doing so, someone is using other people as a means to an end. Kant is vehemently opposed to this. Going beyond that, Kant would oppose pulling the lever on the grounds that it breaks the universal maxim. If you take an action that results in the death of another person, then the basic laws can not exist. If we accept that the maxim is “killing is wrong,” then you can not flip the switch. As by doing so, you are directly responsible for the death of someone. While there are some compelling arguments as to why Kant would flip the switch, I do not believe that any of them stand up to muster.